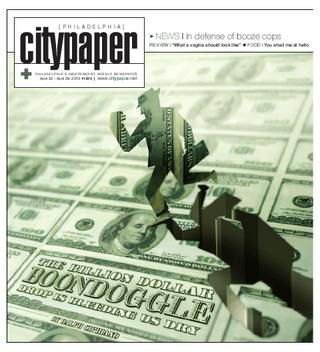

The Billion Dollar Boondoggle: DROP is Bleeding us Dry

By Ralph Cipriano

On Jan. 14, 2012, City Council President Anna Verna is scheduled to retire from office and collect a going-away present from the city — a lump-sum cash bonus of $584,777. But she doesn’t have to stay retired for long.

If Verna runs for office again in 2011 and wins, she can retire for one day, make a deposit at the bank, and then go back to work the next day, Jan. 15, 2012, and resume collecting her salary of $148,090. Or Verna, who will be 80 years old, could stay retired and collect her annual pension of $133,701. Either way, Verna will be a lot richer. And all she had to do to earn that big cash bonus was sign a city contract scheduling a future retirement date she’s perfectly free to ignore.

Under the city’s convoluted pension system, this payout is entirely legal. While Verna’s bonus will be the largest award ever under the city’s Deferred Retirement Option Plan (DROP), it’s just another withdrawal in a billion-dollar run on the city’s already-depleted pension fund.

DROP is the 11-year-old city program that allows municipal employees to double-dip on retirement benefits during their last four years on the job. Employees who sign up for DROP collect their full salaries for a maximum of 48 months, plus a maximum of 48 months of pension benefits paid in the form of a lump-sum cash bonus the day they walk out the door. They also get a minimum of five years of health insurance, plus their regular pensions. And the city has allowed a select few, like Verna, to return to work — at full salary — the day after they retire.

Who would turn down a deal like that?

Records obtained by City Papershow that between 2000 and Feb. 1, 2010, some 6,638 city employees retired under DROP and collected cash bonusesthat averaged $109,277 each — for a total of $725 million. Moreover, 2,107 additional city employees — including Verna and five other City Council members — are currently enrolled in DROP. If those 2,107 enrollees stay in the program the maximum four years, they’ll collect cash bonuses that average $160,525 each, for a total of $338 million.

That’s more than a billion dollars in payouts.

These giveaways are happening as the city faces huge budget gaps into the foreseeable future — $150 million this year — and as Mayor Michael Nutter has proposed new taxes on soda and trash collection, and the city is already diverting revenues from a 1-cent increase in the local sales tax passed last year just to pay for employee pensions.

As a City Paperinvestigation shows, DROP may be a great deal for municipal employees, but for taxpayers, it makes no sense to reward workers with lavish cash bonuses just for showing up — especially when the city doesn’t have enough cash on hand to balance its budget or pay for regular pensions.

■ Runaway train

To gauge the financial impact of DROP, City Paperasked Joe Boyle, a Philadelphia-area actuary — a financial expert who specializes in pension plans and risk management — to do an independent analysis of DROP. The program was originally billed as “cost-neutral” when it was unanimously passed by City Council and signed into law that same day, June 28, 1999, by former Mayor Ed Rendell. This newspaper made the request because the city’s actuarial consultants have either avoided the issue of the cost of DROP, or given contradictory data in their reports.

Boyle analyzed more than 1,000 pages of documents, representing a dozen years of annual reports on the city’s pension system, as well as three reports on DROP. His conclusion: DROP is “a runaway freight train.”

If the city were a business, Boyle says, safeguards enacted by the federal Pension Protection Act of 2006 would have kicked in, and all lump-sum payments and credits for future service would have been cut off until the pension system’s funding level reached 60 percent — meaning, when the pension fund had 60 cents in the bank for every dollar it owes in future pension obligations. As of 2009, the city pension system’s funding level was just 45 percent.

But since this is a government program, those rules don’t apply.

DROP is anything but cost-neutral, Boyle says. It’s also far more expensive than the city’s actuaries have let on.

The traditional way to measure the cost of a pension plan, Boyle says, is to compare the cost of annual contributions to the pension fund (from both taxpayers and employees) to the city’s annual payroll — $1.4 billion in 2009. In 1998, the year before the city adopted DROP, the annual cost of pensions equaled 25 percent of the city’s payroll. By 2009, that percentage had risen to about 41 percent. If you include the annual payments the city makes on a $1.25 billion bond it took out in 1999 — six months before enacting DROP — to bolster the pension system, the true cost rises to 48 percent of the city’s payroll, Boyle says.

He faults the Board of Pensions and Retirement, which oversees the pension fund: “The pension board has completely mismanaged this plan by not addressing the rising costs.”

In the private sector, pension funds cost between 3 percent and 10 percent of companies’ payroll costs. “Having a cost of 48 percent of payroll for pensions would be considered ludicrous,” Boyle says. And, he says, DROP has to be a big factor in those rising costs.

City Finance Director Rob Dubow, also the chairman of the pension board, agrees that the rising cost of pensions is the biggest financial problem facing the city. “It’s gone up dramatically and it puts pressure on our entire budget,” he says in an interview.

However, he says, the city pension board doesn’t determine employee benefits; they’re set by labor contracts and city ordinance. He also disagrees about the role played by DROP — if DROP is a problem, he says, it’s just a small part of the city’s overall pension woes.

■ Compounding errors

The primary goal of DROP programs adopted across the country in the last few decades was to retain veteran police and firefighters who were taking early retirements, collecting their pensions and then moving on to new jobs in the private sector. The thinking was, why not create a legal double-dip that would keep police and firefighters at their government jobs? But here in Philadelphia, the pension board decided to open its DROP program to all city employees regardless of whether they wore a uniform, including even elected officials.

The results have been disastrous.

In 1999, the pension board sent out a letter informing city employees that they were now eligible to enroll in DROP. “PLEASE BE PATIENT,” the letter said. “WE EXPECT SEVERAL HUNDRED APPLICATIONS.”

The first week, more than 1,000 employees signed up. It’s been a stampede ever since, unforeseen by both city officials and the consultants from Mercer Inc. who advised them.

“Sounds like our expectations were exceeded,” says Kenneth A. Kent, the city’s lead actuarial consultant, who has advised pension officials from 1995 until 2010, with the exception of 2005 and 2006. Kent says the economy may have had “an impact on people’s behavior.”

DROP has been a failure with regard to its two originally stated goals: It isn’t cost-neutral, and it hasn’t induced workers to stay on the job longer. Instead, it’s had the opposite effect.

In 1999, the year the city adopted DROP, non-uniformed city employees retired at an average age of 60.1. By 2005, the most recent figures available, non-uniformed employees left their jobs at 57. (Non-uniformed employees make up 67 percent of DROP enrollees.)

“I think it makes sense before you offer a new pension benefit you would understand what the cost would be,” says Dubow, appointed by Nutter in 2008. “I don’t know how they looked at it back then.” He says that Nutter has hired Boston College to study “what impact [DROP] has had on [employee] behavior and costs.”

The city made a few other miscalculations when it set up DROP. Back in 1999, the city’s actuaries projected the pension fund would earn a 9 percent return on its investments every year. That turned out to be overly optimistic. Over the next dozen years, investment returns have averaged less than 4 percent a year.

Kent says that Philadelphia is hardly alone. “If you’re looking at averages statistically,” he says, “a lot of funds have an average return that’s below their assumption.”

City officials also decided in 1999 that half of those projected future earnings should go to people enrolled in DROP. While employees are enrolled in DROP, their future bonuses are collected in a tax-deferred city account that pays a guaranteed 4.5 percent interest — compounded monthly, amounting to 4.59 percent per year. So, even when the economy tanked and the pension plan lost money in the stock market — as it did in four of the last nine years — employees in the DROP program still collected their 4.5 percent interest every month.

Based on the rosy assumption of 9 percent returns, the city’s consultants projected in 2000 that the pension plan’s coffers would swell to $8.5 billion by 2010.

They were off by $4.5 billion.

Similar miscalculations have resulted in legal troubles in other parts of the country for Mercer Inc., the firm that set up Philadelphia’s DROP program. Mercer has been the defendant in negligence lawsuits filed in Milwaukee County, Wis., and in Georgia and Alaska. In Milwaukee, a lawsuit filed against Mercer over another expensive DROP program resulted in a settlement last year of $45 million. The lawyer who negotiated that settlement for Milwaukee tells City Paperit appears that Mercer made the same mistakes in Philadelphia that it did in Milwaukee (see sidebar, p. 18).

■ Reckoning

The city’s pension fund, like its budget, is in dire straits. Last year, Nutter asked the Pennsylvania Employee Retirement Commission (PERC) to declare the city pension fund “severely distressed,” setting the table for a future state takeover. PERC complied, but talks in Harrisburg about the state taking over the city pension fund “did not go anywhere long-term,” Dubow says.

As of 2009, the city owed more than $10 billion in pension obligations to more than 65,000 beneficiaries; for comparison, this year’s city budget is $3.7 billion. The pension fund’s unfunded liabilities equaled $4.9 billion in 2009. That’s not only more than the entire city budget, but also more than the $4 billion that the pension system had left in assets.

The city also can’t afford the annual contributions required to fund its pension system. As disclosed last month in Nutter’s five-year financial plan, the city will defer $155 million of its 2010 pension obligations, and $80 million in additional obligations in 2011. The city will begin paying this money back into the pension fund in 2014, at an interest rate of 8.25 percent.

Even with those adjustments, taxpayers are paying $350 million this year to fund city pensions. According to the mayor’s five-year plan, taxpayer contributions to the pension fund will rise to $480 million in 2011, $563 million in 2012, $687 million in 2013 and $683 million in 2014. The city also is diverting revenues from a “temporary” 1 cent increase in the local sales tax approved last year by the state to raise an additional $580 million between 2010 and 2014 just to pay for the pension costs of Philadelphia municipal employees.

And that’s not the extent of the taxpayers’ bill. A big chunk of the pension fund’s assets came from the $1.25 billion bond that the city floated in January 1999, six months before City Council adopted the DROP program. Then-City Treasurer Corey Kemp denied any connection between loading up the pension fund and the future DROP payments. Kemp said the timing was coincidental, and the city needed the money to prop up its under-funded pension system.

(In 2005, Kemp was convicted of 27 counts of conspiracy, wire fraud, tax fraud and extortion for using his public office for personal gain. He did not respond to a letter City Papersent to the federal prison in Ashland, Ky., where Kemp is serving a 10-year sentence, seeking comment.)

The city took out that $1.25 billion bond — the largest municipal bond issue in state history — at an interest rate of 6.61 percent. The bond boosted the city’s pension funding level to 77 percent by 2001. But that was before the city began paying out hundreds of millions of dollars in lump-sum DROP payments, and before the pension fund’s money managers lost more than a billion dollars last year in the stock market.

Now, the funding level of the pension plan is down to 45 percent, and taxpayers are still paying off that bond. Between 1999 and 2010, the city spent more than $850 million to pay down its debt, but there’s still a way to go. In the 2011 budget, the city will put $114 million toward that debt. And for the following 18 years, taxpayers will pay about $130 million annually. By the time the 30-year bond is paid off in 2029, taxpayers will have spent nearly $3.5 billion.

■ Material costs

The legislation that created an experimental DROP program in 1999 stipulated that “the impact of the plan will not result in more than an immaterial increase” to the city’s annual cost of funding pensions, and if it did, the program was supposed to be scrapped.

It did. And it wasn’t.

In 2004, the Board of Pensions and Retirement voted 5-3 to make DROP permanent, even though the city’s actuary had determined that the first four years of the program had added $64 million to the pension fund’s debts (the city finance director put DROP’s bill even higher, at $113 million).

The pension board is composed of four appointed city officials, four union representatives and the city controller, an elected official who often acts as a tiebreaker.

In 2004, a representative of then-City Controller Jonathan Saidel sided with four union representatives in the vote that made DROP permanent. Saidel told City Paperin 2004 that he figured the $64 million was an “immaterial increase” because it amounted to less than 1 percent of what the city owed at the time in future pension obligations, $6.7 billion.

Since then, the city’s actuaries have refused to reconsider the issue. “It was the board’s determination … that the DROP costs represented an immaterial increase in the City’s normal cost of annually funding the Retirement System and the program was continued,” declared actuaries Kent and Christian Benjaminson of Cheiron, a financial services firm based in McLean, Va., in their most recent DROP “program study,” in April 2008. “Our report does not revisit the financial implications or the basis of the Board’s decision,” they wrote, in bold print.

“There was no requirement after that point in time to conduct a similar analysis,” Kent explains in an interview.

In that same 2008 report, the actuaries made the confusing claim that the DROP program had either saved the city as much as $62 million, or cost it as much as $203.4 million. “Our expectation is if there were no DROP, the system’s experience would be somewhere between those two values,” they wrote.

Kent says the actuaries presented a wide cost range in their report because they did not know for sure how DROP was affecting employee behavior. There was a “large rush” at the beginning of the program, Kent says, but lately, “it’s dropped off a bit” and the employees enrolled in the program “are definitely not staying the full four years, on average.”

Dubow defends Kent’s work for the city that started while he was employed by Mercer and continued after he joined Cheiron.

“We are actually very comfortable with the work he’s done for us,” Dubow says.

But Boyle, the actuary who analyzed DROP for this newspaper, calls Kent’s estimates “voodoo economics, because it’s completely unclear in their reports how the city’s taxpayers will ever benefit from DROP.”

At City Paper’srequest, Boyle charted the annual cost of the DROP payouts. According to his calculations, at the height of the DROP exodus, the program created an average annual liability of $1 billion a year between 2002 and 2006, before declining to $825 million in 2007 and $652 million in 2008.

Moreover, Boyle says the city could have saved about $240 million over the last decade just by cutting the fat out of DROP and the pension system’s bloated administrative costs. Between 2000 and 2008, the city spent more than $60 million to pay that guaranteed 4.5 percent interest rate to every employee enrolled in DROP. Had the city cut that rate to a more reasonable number — say, 1.5 percent, more than you’d get in a money market today — taxpayers would have saved $40 million, Boyle says. (Kent points out that that 4.5 percent interest rate is set by city law, and can only be changed by City Council.)

Additionally, between 1998 and 2008, the city spent $72 million on in-house administrators to oversee its pension plan. Had the city brought administrative costs in line with industry standards, Boyle says, it could have saved as much as $48 million.

Over the last dozen years, the city has spent more than $200 million on outside investment managers and consultants. Last year, when the city’s pension fund recorded a loss of $1.2 billion in the stock market, the city spent $28 million on 150 money managers, according to city officials.

According to Christopher McDonough, the city’s chief investment officer, “It’s not uncommon” for cities to use multiple investment managers.

Boyle, however, says the city is wasting money on all those money managers, and could have saved $150 million over the last dozen years by investing in standard indexes, such as the S&P 500 or the Barclay’s Aggregate Bond Fund. While the city’s pension fund managers and consultants averaged an annual return on investments of 3.91 percent over that dozen-year period, Boyle’s figures show that a conventional 60-40 investment split of stocks and bonds would have performed slightly better, with an annual return of 4.12 percent.

McDonough says that a more passive investment strategy “is something we have looked at and continue to look at.” He says one problem with passive strategies is that they require a static cash flow, while the city’s revenue situation is constantly changing.

Dubow adds that “a full passive approach” to investments would “produce savings,” but also “would have cost us returns.”

While Boyle’s investment-return statistics are based on a 12-year review, the city did its own study based on a 10-year review. The city’s study shows their money managers averaged an annual 3.73 percent return, compared to a 60-40 investment split that it calculated at just 1.96 percent in annual returns.

■ The Double Dip

If Council President Anna Verna does decide to retire for a day, she’ll be following in a colleague’s footsteps. Councilwoman Joan Krajewski retired for a day in 2008, collected a $274,587 DROP bonus, and went back to work the next day. The watchdog group Committee of Seventy challenged her actions. But last year, City Solicitor Shelley Smith issued a legal opinion that defended Krajewski. DROP doesn’t discriminate against elected officials, Smith opined.

The decision to enter DROP, however, was supposed to be “irrevocable.” The first question in the DROP brochure the city still distributes to employees asks, “What if I elect to participate in DROP, and then decide I don’t want to retire after four years?”

The answer: “Your election to participate in DROPis irrevocable. Once you officially enroll in DROP, you must retire within four years of your enrollment date.”

But not everybody has to play by those rules. Kra-jewski is one of 40 high-profile officials in the past 11 years that the city has allowed to retire for a day, collect their DROP bonuses, and go back to work. Mayor John Street granted the first two exceptions in 2003: He exempted his choices for police commissioner and deputy police commissioner, Sylvester Johnson and Robert J. Mitchell. Street said the two cops were too valuable to let them retire. But they got to keep their retirement bonuses.

The city then began exempting employees on a case-by-case basis. Former City Solicitor Romulo L. Diaz opened the door for elected officials by allowing Krajewski and City Commissioner Marge Tartaglione to run for re-election in 2007, even though both were enrolled in DROP. (Last month, City Council voted unanimously to eliminate elected officials from enrolling in DROP, closing that loophole for all future elected officials — but not for current officials. This is, however, political theater: State lawmakers have already passed a law to reform Philadelphia’s DROP program by eliminating elected officials from it.)

Besides Verna, five other City Council members are presently enrolled in DROP and are scheduled to retire in 2011 or 2012: Councilman Marian Tasco, slated to collect $478,057; Councilman Frank DiCicco, $424,646; Councilman Jack Kelly, $299,163; Councilwoman Donna Miller, $195,782; and Councilman Frank Rizzo, $194,517.

Verna entered DROP on Jan. 14, 2008, signing a contract that required her to retire over the next 48 months. She had 56 years in the city’s employ, including eight terms on City Council. Because of her many years of service, Verna qualified for a pension equal to 100 percent of her salary, or $133,701. (This year, Verna’s salary was raised to $148,090, but her annual pension will stay at $133,701. Employees in DROP don’t get credit toward their pensions for additional years on the job, or any raises after their enrollment.)

Verna hasn’t made up her mind yet whether she’s going to run again, because she’s working day and night on the city’s budget crisis, says Tony Radwanski, City Council’s communications director.

Verna declined to discuss her DROP bonus with City Paper.

Verna has previously defended her cash bonus of $584,777. “I’ve been working for the city for years and I have put money into the pension program,” Verna told Philadelphia Weeklylast year. “The DROP money is, in essence, my money. I’m not asking the city, as has been portrayed, to give me a satchel of money and I’m going to walk out of City Hall. That’s my money and I’ve worked hard for it.”

In other words, she’s entitled. But is that money in DROP really her money?

Hardly. A closer look at how DROP operates reveals why the program is so draining on the pension fund.

The problem is that the pension plan remains so under-funded. City employees make relatively minimal contributions to the fund that pays for their pensions — between 1.8 percent and 7.5 percent of their salaries. The city then contributes about 33 percent of the employees’ salaries to the pension fund. But when employees enroll in DROP, the city treats them as if they just retired, and begins paying into a tax-deferred account an amount equal to 100 percent of each employee’s annual pension, plus the guaranteed 4.5 percent interest rate (compounded monthly).

So, every time an employee enrolls in DROP, the pension fund takes a bigger hit.

In Verna’s case, if DROP did not exist and she retired on Jan. 14, 2012, during her final four years on the job she would have earned a total of $575,731 in salary. But she also would have had to contribute 7.5 percent of her salary to the pension fund — $10,794 a year or $43,179 over four years. During that same four-year period, the city would have made contributions to the pension fund on Verna’s behalf equal to 31.7 percent of her annual salary, according to city pension officials, $42,249 a year or $168,996 over four years. Without DROP, Verna’s salary and pension benefits over four years — minus the amount she would have contributed to the pension fund — adds up to $701,548.

With DROP, Verna continues to draw the same salary — $575,731. But there’s another benefit to being enrolled in DROP — she no longer has to contribute to the city pension fund. For Verna, that amounts to a 7.5 percent raise of $10,794 a year or $43,179 over four years. Meanwhile, the city continues to pump 100 percent of her annual pension — plus the guaranteed 4.5 percent interest rate — into a tax-deferred account, about $146,194 per year or $584,777 over four years. That means that over the four years she’s in DROP, between her salary, her DROP cash bonus and the money she no longer has to contribute to the city’s pension fund, Verna’s double-dip will cost the city $1,203,687.

That’s an extra $502,139, for just one of 8,745 past and present DROP enrollees.

And how much of that was her money? During Verna’s first 56 years as a city worker, her contributions to the pension fund amounted to slightly less than $150,000 — about 25 percent of her DROP bonus.

In response, finance director Dubow says that the money “being deposited into that DROP account is the pension payment [employees] have earned under the city’s pension system.”

■ Hidden costs

There are other hidden costs to DROP and the city’s pension plan. Under Social Security or most private pension plans, if you retire up to three years before you turn 65, your pension is reduced by 20 percent. But in Philadelphia, there’s no penalty for retiring early.

And, in contrast to Verna, that’s what most DROP enrollees are doing.

The most recent statistics available show that the city’s non-uniformed employees are retiring at an average of 57 years of age, while cops and firefighters are retiring at an average age of 52.8. That’s another problem for taxpayers, because DROP retirees are going out the door long before Medicare kicks in at age 65, and every retiring Philadelphia employee gets a minimum of five years of health insurance.

A 2008 study by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that of the 10 major cities it surveyed, Philadelphia paid the most in health care costs per retiree — $9,150 in 2006, nearly twice the median cost in that survey, $5,792.

That same study reported that Philadelphia’s non-uniformed employees make relatively small contributions to the pension fund: only 1.85 percent of their annual salaries, compared to 7.5 percent in Boston, 8.5 percent in Chicago and 9 percent in San Francisco. (The 5 percent that uniformed employees and 7.5 percent that elected officials pay is also less than their peers in other major cities.)

Dubow points out that the city recently got the police union to increase officers’ annual pension contributions by 1 percent. He says the city is seeking similar concessions in ongoing contract talks with three other city unions.

But that doesn’t satisfy critics like Boyle, the actuary. He says the pension board is abdicating its primary responsibility — protecting the pensions of the fund’s 65,662 beneficiaries — in favor of an “investment scheme” that benefits the 8,745 past and present DROP enrollees. By continuing to pay DROP cash bonuses with money it simply doesn’t have, Boyle says, the city jeopardizes the health of its entire pension plan.

Dubow says the “investment scheme” label is “not fair.” “The DROP is about timing on when people start getting their retirement benefits,” he writes in an e-mail. “How does that make it an investment scheme?”

Boyle says he’s worried about beneficiaries like his mother, an 81-year-old widow who lives off the $18,000 annual city pension left behind by Boyle’s father, a civil engineer.

DROP enrollees are also a burden on the pension system because they’re taking home more than their share of benefits. Only 13 percent of the pension’s beneficiaries are enrolled in DROP, but these employees are departing City Hall with 25 percent of the pension fund’s assets.

Dubow says that’s an “apples to oranges” comparison. “The appropriate comparison would be pension payments to DROP participants to all participants over the same period.”

Those figures, however, are not available in any of the city’s actuarial reports, Boyle says.

Besides Council President Verna’s top-rated haul, other big DROP bonuses are scheduled to go to Carl Ciglar, deputy executive director of the Philadelphia Parking Authority, who will collect $524,529; Chief Police Inspector Richard Bullick, $514,719; and Chief Police Inspector Joseph O’Connor, $507,520. (All are scheduled to retire in 2013, and all declined to comment for this story.)

But you don’t have to be at the top of the city pay scale to reap a windfall under DROP. Take Margaret Taylor, a city crossing guard who earns $51.48 a day. When she’s scheduled to retire on Jan. 24, 2014, Taylor will receive a DROP cash bonus of $58,257.

Because the city counts overtime in determining DROP payments, Charles Robinson, a semi-skilled Streets Department laborer who draws a salary of $34,867 but who racks up an average of $22,981 in overtime, will leave his job in 2011 with a check for $172,373. Ernest Valentin, a $43,467-a-year heavy-equipment operator who earns an average of $23,032 in overtime, will retire in 2012 and collect $208,378. And Nordine Harris, a $40,816-a-year correctional officer who earns an average of $60,794 in overtime, will retire in 2011 and get a DROP bonus of $330,813.

If DROP is, as Boyle says, a runaway freight train, where’s it headed? “We’re going toward bankruptcy,” Boyle says. “And a state takeover.”

(editorial@citypaper.net)

SIDEBAR

In recent years, both the city of San Diego and the county of Milwaukee adopted expensive DROP programs, just as Philadelphia did. But in San Diego and Milwaukee, publicity over big DROP bonuses sparked taxpayer revolts, criminal indictments, court battles, recall drives and a negligence lawsuit against an actuarial consultant — Mercer Inc., the same company that set up Philadelphia’s DROP — that resulted in a settlement of $45 million.

Philadelphia, it seems, could learn a lot from those experiences. But, so far, it hasn’t.

San Diego passed its DROP program in 1997. Like in Philadelphia, the San Diego DROP was supposed to be cost-neutral. In 2009, the mayor and city council rescinded the program for all new employees.

“It was an interim program that was supposed to have a cost-neutrality study before it was approved,” Jan I. Goldsmith, the San Diego city attorney, tells City Paper.Instead, San Diego officials waived that study and made the program permanent without knowing the price tag.

In Philadelphia, DROP was made permanent in 2004, even though no in-depth study was ever done about its future cost or effect on employee behavior. The program was supposed to be cost-neutral, but had already cost taxpayers at least $64 million.

In San Diego, DROP also provoked a legal war between the city and its police union that ended when a federal appeals court ruled that the city had the right to make DROP cost-neutral by reducing the salaries of workers enrolled in the program and a state superior court judge allowed the city to reduce the interest rate paid to DROP employees.

That wasn’t the only fallout. Members of the San Diego pension board that approved DROP were hit with two waves of indictments: Six board members were charged with conflicts of interests for approving a program from which they would directly benefit.

In January, an appeals court dropped charges against five of six pension board members, ruling that they did not have an actual conflict because their interests in approving DROP were the same as the city workers they represented. But the San Diego pension board isn’t clear yet. Three pension board members still face fraud charges in a federal indictment.

“San Diego has already had our crisis and we’re dealing with it,” Goldsmith says. “I just wish you luck, because these pension issues are difficult.”

Goldsmith’s counterpart in Philadelphia, City Solicitor Shelley Smith, declined to comment on whether actions undertaken by San Diego — or Milwaukee County — could be done here.

In Milwaukee, county officials filed a federal negligence lawsuit against Mercer Inc., the consultant that set up DROP programs both there and in Philadelphia, and last year collected a $45 million settlement. In their suit, Milwaukee county officials alleged that they had not been properly advised about the full cost of lump-sum DROP bonuses and related benefits.

“The county would have pulled the plug,” the lawsuit alleged, “if Mercer had warned that the costs were too high for the county to pay or that it hadn’t studied the costs.”

After a brief review of Philadelphia pension and DROP records, James Southwick, the Houston attorney who negotiated Milwaukee’s $45 million settlement with Mercer, says he recognizes a familiar storyline.

“It looks like here again, as in Milwaukee, Mercer blew it in terms of how it [DROP] would affect employee behavior,” Southwick says.

His advice to Philadelphia officials: Call me. “You need to give it a look,” Southwick says. “It’s certainly worth it for the city to talk to lawyers and see, ‘Do we have a claim here?’”

The big question, Southwick says, is, “Were we given bad information? Did [DROP] blow up in our face because we had been given bad information?”

Milwaukee County isn’t the only government with complaints about Mercer, a giant human resources company with 4,000 employees and 150 offices around the world. In December, The New York Timesreported on what it described as “a bombshell of a lawsuit,” in which the Alaska Retirement Management Board, a state agency, is suing Mercer for allegedly making repeated mistakes in setting up the state’s retirement plan for its workers, and then attempting to cover up those mistakes.

In response, according to the Times, Mercer conceded making an error in a calculation that it used to determine the cost of numerous employees’ health care benefits, and said that its failure to disclose that error was “a mistake in judgment … not consistent with the company’s corporate culture.” The state agency, however, says that mistaken calculation and the attempts to cover it up resulted in the state agency under-reporting the contributions needed to sustain the pension fund by $2.8 billion. So the state agency is seeking $2.8 billion in damages in a federal trial scheduled for July in Juneau. If the state wins, the Timesreported, Mercer could also be liable for punitive damages.

In Philadelphia, city officials acting on Mercer’s advice were wrong on several projections — on how many employees would sign up, on whether the program would be cost-neutral, on whether it would induce workers to retire later — all proved erroneous.

Attorney Southwick suggests that Philadelphia consider hiring a new actuary.

■ Since 1995, with the exception of two years, Phil-adelphia has primarily relied on the counsel of one expert. Kenneth A. Kent set up the Philly DROP as a Mercer employee, before he became a consulting actuary to Cheiron of McLean, Va., Phil-adelphia’s current actuarial consulting firm. Between 2001 and 2007, the city paid $2.3 million to Mercer Inc., and from 2008 to 2010, another $834,086 to Cheiron.

In an interview, Kent defended his work in Phil-adelphia. He says it was up to the pension board to anticipate how many employees would retire under DROP, although Kent did advise pension board members on that subject, and is presently doing a study on how DROP affected employee behavior. He adds that over the past decade, “If you’re looking at averages, statistically a lot of funds have an average return that’s below their assumption.”

Philadelphia officials have remained loyal to Kent, even though Mercer didn’t.

While at Mercer, Kent became embroiled in another negligence lawsuit filed in federal court in Atlanta, Ga., by the United Food and Commercial Workers Unions and Employers Pension Fund, which represented 130,000 grocery store workers. In the lawsuit, the pension fund charged that because of “incorrect information” received from Mercer, the fund had “increased benefits when it should not have,” and that Mercer had “underestimated, omitted or mispriced” future liabilities by “tens of millions of dollars.”

Kent was the lead actuary on the account from 1999 until Mercer fired him in December 2004; according to court papers, the union pension fund was “Mr. Kent’s biggest account.”

“According to Mr. Kent … the cost of the benefits promised to participants exceeded the employer’s contributions and the fund’s investment returns were insufficient to make up the shortfall.”

In a 2004 letter to the pension board trustees, Kent wrote that “programming errors in [Mercer’s] val-uation system” had resulted in a miscalculation that “undervalued the fund’s liabilities by $54 million.”

Mercer offered to settle for $2.25 million, but was turned down by the pension fund. The case went to trial in 2008; ultimately, a federal jury found the union and Mercer equally liable for negligence, and awarded no damages.

According to court papers filed in that lawsuit, “In early 2003, Mercer stripped Mr. Kent of his supervisory responsibilities, denied him any future promotions and limited his salary increases. To remain employed, Mercer required Mr. Kent to assign another senior consultant to each of his clients and fully comply with Mercer’s quality control procedures. Mercer fired Kent due to his failure to adequately satisfy these conditions. Termed a ‘downsizing’ to clients, this moniker was merely Mercer’s ‘party line.’”

In an interview, Kent says he has dedicated his career to “maintaining the highest professional standards of practice and integrity.” He says the allegations in court papers were “full of inaccuracies,” that he lost his job as part of a downsizing at Mercer, and that he was never fired. He says he was never stripped of supervisory responsibilities and that he continued to receive raises. He adds that the client was so upset about Kent’s departure that they promptly fired Mercer.

The city continues to defend Kent. “We are actually very comfortable with the work he’s done for us,” says Rob Dubow, city finance director and chairman of the city pension board.

■ In Milwaukee, angry citizens staged massive petition drives that gathered more than 70,000 signatures. They forced the resignation of County Executive F. Thomas Ament, who was scheduled to retire in 2008 with a $2 million cash bonus, but resigned under fire in 2002 without any DROP money. Citizens also voted to recall seven members of the county board of supervisors who had voted for DROP.

In 2004, the county’s human resources director — the creator of Milwaukee’s DROP program — was indicted and pleaded no contest to one felony count of misconduct in office, and two additional misdemeanorsrelated to his role in the pension deal, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. He was fined $11,000 and sentenced to 30 days in jail.

In contrast, here in “corrupt and contented” Philadelphia, as muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens famously described the city in 1904, there has been no citizen uprisings over DROP. Rather than reform the program or investigate the circumstances under which it was made permanent, elected officials, such as former Mayor John Street — who told City Paperin 2003, “We will ultimately end the DROP program” — have joined the parade down to the municipal feeding trough.

Street retired in 2008 and collected his DROP bonus of $456,963.

Three members of the city pension board that voted to make DROP permanent in 2004 have also retired and collected DROP benefits. Two former pension board members — city Personnel Director Lynda Orfanelli, who retired in 2006 and collected $367,041; and Charles Johnson, a union representative on the pension board, who retired in 2001 and collected $52,222, three years before he voted as a pension board member to keep DROP. Carol G. Stukes of District Council 47 retired in 2009 as a police officer under DROP and collected a $230,208 bonus. Stukes still serves on the pension board as a union rep. She did not return a call from City Paperseeking comment.